- Home

- Simon Gilbert

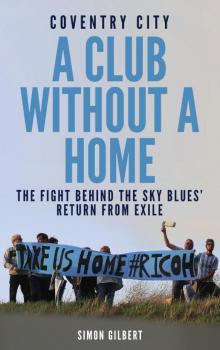

Coventry City

Coventry City Read online

First published by Pitch Publishing, 2016

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

© Simon Gilbert, 2016

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 978-1-78531-210-6

eBook ISBN 978-1-78531-269-4

---

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

Goodbye Highfield Road

Hello Ricoh Arena

Sisu the saviours

Held to Ranson

‘Best board ever’

Charity begins at home

Keeping council

Administration

Highfield Road II

Sent from Coventry

Jimmy’s Hill

Theatre of broken dreams

#BringCityHome

Sting in the tail

Photographs

Acknowledgements

THIS book would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of my beautiful pregnant wife, Carly. Her patience was stretched to the limit as I spent countless days and nights hunched over a laptop rather than giving her the attention she deserves.

I would also like to thank my soon-to-be-born son for inspiring me to produce something I hope he will be proud of when he’s old enough to understand.

Thanks to my parents, family and friends for offering words of motivation when there seemed to be no end in sight.

Some gratitude also goes to my loyal canine companion, Tippy, who was always there with a smile on her face and a wag in her tail whenever my spirits waned.

There is special appreciation for the efforts of Robert Seeley and Daniel Gill, who tore through the first draft in record time.

Thank you to those interviewed for the book: Alan Payne, Bob Ainsworth, Bryan Richardson, Carl Baker, David Conn, Gary Hoffman, Geoffrey Robinson, James Whiting, Joe Elliott, John McGuigan, Jan Mokrzycki, Jordan Clarke, Paul Fletcher, Peter Knatchbull-Hugessen, Steve Brown and Steven Pressley.

Thanks also to Mark Labovitch and Tim Fisher for providing some excellent narration over the years.

I would also express my eternal gratitude to former Coventry Telegraph editor Alun Thorne who hired me and provided the backing needed to report a challenging and complicated subject – often in hostile conditions.

That support has continued under the editorship of Keith Perry, who has enabled me to take undisputed ownership of this subject.

Thank you to many of my current and former colleagues at the Coventry Telegraph, who have been forced to pick up the slack when my energies were focused on CCFC – or sub-edit the thousands of words of copy filed on this subject.

Appreciation also goes to Trinity Mirror for allowing me to use the archived news coverage in the Coventry Telegraph.

Further thanks to Steve Phelps, who has helped steer me in the right direction as I took my first steps into the world of becoming an author.

Thanks also to Duncan Olner for the cover design as well as Paul and Jane Camillin and the entire Pitch Publishing team for putting their faith in me to deliver this title.

But, most of all, thanks to the Sky Blue Army. I’m your biggest fan.

Chapter One

Goodbye Highfield Road

HOW did we get here? A question all too familiar to Coventry City FC supporters who find their team languishing in the third tier of English football and with no ground to call their own.

This once-proud club, with over 130 years of history and 34 consecutive years in the English top flight, has ultimately ended up homeless. At one point, the club even left Coventry for over a season but, thanks in no small part to the passion of its fans, the club has at least returned to its home city.

But where did it all go wrong?

In order to provide the answers, we have to go back almost 20 years to the very beginning of the club’s modern-day problems.

In 1997, Coventry City FC chairman Bryan Richardson unveiled his vision for the future of the Sky Blues.

His idea was undoubtedly ground-breaking, ambitious and exciting. But it also carried huge risks – risks Sky Blues fans are still paying the price for today.

At the time, few spoke out against the plans for a flashy new stadium complete with sliding roof and retractable pitch. As supporters, we were dazzled by the prospect of what could be and promises that Coventry City FC would be self-sustainable, with the income needed to build a world-class team and compete with Europe’s elite.

But, with the benefit of hindsight, it’s a different story today.

It’s easy to see why so many of us were taken in. This was a period when the club was spending money like never before. A board led by Richardson, supported by Mike McGinnity and Derek Higgs and bankrolled by Geoffrey Robinson, had put their money where their mouths were in a bid to take Coventry City into Europe.

Footballers recognised across the globe donned the sky blue of Coventry City. It was a period when the team was graced by glittering international stars such as Robbie Keane, Gary McAllister and Mustapha Hadji.

Life as a Coventry City fan was good back then – and Richardson had promised things were about to get a whole lot better.

Highfield Road was a much-loved ground, but it was limited by its geography. The residential location meant it had little room to expand, and there was not a great deal of space to develop other facilities which could provide the club with non-matchday income.

The board believed the club had outgrown its traditional home and set about identifying a site to build a new one as part of a project which would be supported by Coventry City Council.

That was the former gasworks site, in Holbrooks, and plans for a 40,000-seater stadium were soon drawn up by Coventry architect Geoff Mann. Billed Arena 2000, it included a retractable roof and a sliding pitch, with the aim of staging World Cup matches should England’s bid to host the tournament in 2006 become successful.

In a glossy brochure produced to promote the plans, Bryan Richardson declared the development would ‘make a national impact on sport and leisure’.

He added: ‘We are clear this will be a venue vying for World Cup football, world championship boxing, tennis tournaments, hockey and equestrian events, as well as major concerts and exhibitions. We believe the project will provide the city with a landmark it can be proud of.

‘It is essential we seek ways of increasing our current Highfield Road capacity, whilst at the same time increasing in a substantial way the income we receive to allow us to compete with bigger clubs.’

That same brochure also included comments from the then leader of Coventry City Council, John Fletcher, who waxed lyrical about the project he predicted could be a ‘vital shot in the arm for the area’.

He added: ‘The whole idea is spectacular. It has massive potential. We are very excited but must also ensure proper scrutiny of the proposals to make sure the right decisions are made for Coventry.’

Geoffrey Robinson said the entire board backed the project from the very beginning.

He said: ‘It was ve

ry exciting. Bryan was a tremendous entrepreneur. The original idea was very risky from the beginning, but we all went along with it.

‘It relied on a level of commitment and goodwill from the council that never really came to fruition.

‘Both sides were to blame as it went along, but it did presuppose that it would be a successful development for the council and the club with goodwill, give and take all the way through.’

John McGuigan, then development chief for Coventry City Council, said the authority always saw the project as an opportunity to regenerate a downtrodden part of the city.

He said: ‘For many years, the football club had been looking for a new ground. Highfield Road was a model of what a football ground should be, but the site was hugely restricted by location.

‘About half the big home games they had, they were having to lock people out – when teams like Manchester United and Chelsea came to town.

‘Their ability to grow non-football revenues was hugely limited.

‘My understanding is they had looked at sites around Warwick University, around Ansty and some derelict sites in the north of the city. But none of them were big enough.

‘The council in the 1990s had a clear idea that the city had to grow. We had a boom city that had hit bad times in the 1970s and it had taken all of 20 years to stabilise that.

‘We had to put energy into the north of the city. People who came to Coventry off the M6 were greeted by a disused colliery and a derelict gasworks.

‘For 30 years, there had been all sorts of things suggested for the gasworks site, but none of them were big enough to make it work.

‘The Ricoh was the key to a project that aimed to regenerate both sites in the zone labelled the North Coventry Regeneration Zone.

‘There wasn’t a district centre in the north of the city and we were anxious to help the football club relocate from Highfield Road.’

He added: ‘We made it very clear from the beginning we were not interested in replacing a football stadium with a football stadium.

‘We wanted a venue that could host concerts and attract big business conferences. We wanted a landmark building that could change the image of the north of the city from that of a derelict gasworks.

‘That’s why the idea of bidding to host World Cup matches came up. To do that required a minimum capacity of 40,000.

‘The design originally was two tier, the idea being there would be a huge curtain that would be drawn across the upper level when you didn’t need the whole thing. But that was too big.

‘A retractable roof and pitch allowed it to be turned into an exhibition hall.

‘One hundred metres by 70 metres of grass stood in an 18in-deep concrete tray. It would have weighed about 12,000 tonnes and sat on Teflon pads.

‘Six days a week, when it wasn’t being used, it would have sat outside on the south of the ground so it could get the sunlight.

‘There was going to be a train station under the car park.

‘When Bryan Richardson showed us the plans, our initial reaction was, “you are joking?”

‘There was only one other similar facility in the world, the Gelredome in Arnhem, Holland, which we went to visit.

‘That was only a 20,000-seater stadium, but the idea of the Teflon pads was there.

‘We always had misgivings about the idea because it was predominantly still a football stadium.

‘If we were trying to bring a big exhibition to the city, we would not be sure if the venue would be available because the club could be playing a midweek game or a cup game. That meant the non-football income was in doubt.

‘But if England had won its bid to host the World Cup, we would have gone for that.’

Speaking during an interview with the BBC in 2012, Bryan Richardson made it clear he felt the club had no option but to build a new stadium.

He said: ‘It was the only chance we had.

‘We averaged 19,000 a game and brought in receipts of £5m a year. Arsenal and Manchester United make that in one match now. Our break-even attendance at the time would have been 83,000.’

In 1998, the club successfully applied for planning permission to demolish Highfield Road and build a new stadium at the gasworks site. But, as costs for the mammoth project increased, the club’s board decided to sell Highfield Road for around £4m in 1999 and lease the ground back.

This was a pivotal moment, and one which Geoffrey Robinson later described as ‘a disastrous mistake’.

He said: ‘We sold Highfield Road outright in order to do it.

‘The whole thing, as it turned out with hindsight, was a disastrous mistake for the club. It needn’t have been. The original deal was great.

‘Looking back, I think we should have got to the point where we had the money before we sold Highfield Road.’

He added: ‘We got a good price. It was the whole board’s decision to sell.

‘It was a big decision and a gamble that everybody decided to go for. Football was in one of its big upward swings.

‘If you wanted to stay in the Premier League, you needed your own modern stadium.’

John McGuigan said: ‘The football club put in a joint planning application for Highfield Road and the Arena at the same time in 1998.

‘They had to be put in at the same time because if you were removing a sports facility you had to demonstrate it would be replaced, otherwise Sport England – the governing body at the time – could have vetoed the application.’

He added: ‘The disposal of Highfield Road got about £3m to £4.5m for housing. But the bank took that straight from them.’

The scale of the project, and the chance for Coventry to host World Cup matches, may seem like pie-in-the-sky looking back, but it was a very real vision at the time – and one which attracted the attention of the football world.

John McGuigan added: ‘The FIFA hosting committee visited us. I went down to London with Bryan for a big slap-up dinner.

‘I was on the main table with Hugh Grant, Bryan and Kevin Keegan. There were 80 people at the dinner and the room was full of the big names in English football.

‘It shows how much the design of the stadium had attracted attention.

‘But England didn’t win the World Cup [bid] and we had to revisit the whole issue of the design and how it would work.’

One year later, England’s bid to host the 2006 World Cup failed and the wheels began to wobble on the new stadium project.

The plans had to be redrawn, the original designs were too expensive and did not offer enough potential for non-matchday revenue. They eventually moved towards the design we recognise as the Ricoh Arena today.

The club was in serious financial trouble not least because the Co-Op Bank, which had huge amounts of money invested with football clubs, had launched a drive to reduce its level of lending – including to Coventry City.

John McGuigan said: ‘At the time the club was £60m in debt, including a £20m loan from Geoffrey Robinson.

‘The Co-Op were the football club’s bank, and at that time they had started a drive to lower the debts of all the football clubs on their books.’

Geoffrey Robinson has never confirmed exactly how much he committed to the club during his time on the board, but he did indicate it was tens of millions.

He said: ‘I regret the costs obviously. But I have regrets in the sense that I didn’t succeed. We let the fans down dreadfully.

‘That’s my overriding regret: we failed, we failed the club. We failed in our objectives to get the club to stay up and the finances straight – we didn’t do either.

‘It was a golden period when we got involved in the late 1990s. My first money went in in 1996. Nobody regrets the great times, the players, the fans above all.

‘I made the money available far too easily in retrospect. I trusted people far more than I should have. But that’s not central to the big issue.

‘I put £10m in the club and we had Whelan, Kevin Richardson, Darre

n Huckerby – a group that kept us going for five or so years. We didn’t quite make it, but they were great years. I don’t regret those.’

The club had a preliminary agreement to buy the gasworks site from British Gas and Bryan Richardson recruited Dutch construction firm HBG to decontaminate the site ready for the new stadium to be built.

But catastrophe struck on 5 May 2001 – a day many Sky Blues fans will look back on as the single biggest moment in the club’s post-war history. The club was relegated from the Premier League. With relegation came a dramatic drop in income. It marked a downturn in the club’s fortunes which many will argue continues today.

But the biggest implication at the time was that Coventry City’s financial troubles were severely worsened. This hugely undermined the club’s ability to continue with the new stadium project. Reports at the time suggest the club suffered debts in the region of £60m, including bank loans and loans from board members.

Geoffrey Robinson said: ‘We had failed. We always threw everything at staying up.

‘You can’t blame any of the club’s debts on the stadium, I don’t think. They were big already and the stadium didn’t give us the lift we needed.

‘To stay in the Premier League is a real big art. We gambled on staying up, and we failed.’

HBG came to the football club for payment as the final gas tower was demolished at the site in 2002, but there was a problem. The club had no money, and it transpired British Gas still owned the gasworks land as the club’s preliminary deal to secure the site had never been formalised.

The Dutch construction firm went over the club’s head to secure the land from British Gas, before convincing the council to purchase the 70 acres of land from them for £20m or risk losing the entire stadium project. That same weekend, the council sold the land to Tesco for £60m after Bryan Richardson had negotiated the deal with his personal friend and Tesco chief executive Sir Ian MacLaurin – a deal Bryan Richardson is understood to have collected a £1m bonus for.

John McGuigan said: ‘HBG, a Dutch construction company, built the original stadium in Arnhem. They were really the only people we could trust to build this stadium.

Coventry City

Coventry City